Oh, hello there—

This essay is a complete crash out. I would apologize, but I’m too demoralized.

I’m going to start this entry with a some disclaimers, since Broadway fans are mean and chronically under-occupied.

I’m not a theater critic. I know slightly more about theater than the average American, which is to say, fuck all, really. My deep, trenchant loathing for BOOP! The Musical is also not the sole focus of this piece, despite it being the sole focus of my conversational repertoire for the months of April, May, and June (apologies, friends).

Everyone involved in the production of BOOP! The Musical did a fabulous job. This essay isn’t an indictment of any individual cast or crew members’ efforts.

All of my AI accusations are alleged. I cannot prove or disprove them, and neither can you.

I am writing about BOOP! The Musical not because I think it’s all that worthy of attention or critique, but because it serves as a window into the genre-variegated collapse of the American culture sector over the last decade. Also, the title is funny to type.

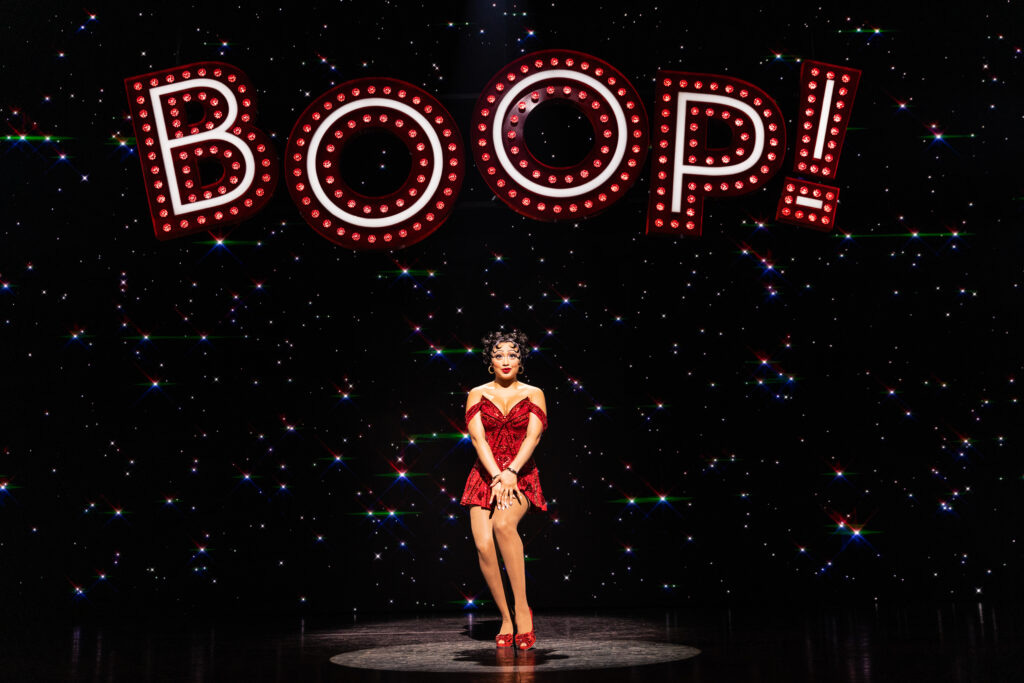

Part I: We Could See BOOP!

My best friend is a media professional and Broadway enthusiast, so when I want to cheer her up, I buy tickets. My last expenditure of this variety manifested as seats in the mezzanine of BOOP! The Musical, a sparkly, tap-dancing revue that migrated from Chicago to the Broadhurst Theater in Times Square on April 5, 2025. The rumors are true; I did, in fact, purchase these stubs after drinking four Aperol Spritzes really, really fast—no research was conducted, in other words—but I’m no stranger to schlock, and expectations felt appropriately low.

It’s a musical about Betty Boop, for fuck’s sake. Her catchphrase is noise. Surely a Zeigfield Follies rip-off wouldn’t send me into a six week depression so corporeal as to inspire my boyfriend’s invention of the term “Boopfluenza” ! Surely not!

Reader, BOOP! The Musical wasn’t bad. It wasn’t even garbage. On the contrary, it was a sensorial argument against the form, a shabby insult to the historical precedent that frames and shapes the discipline of musical theater. I spent Act I with my mouth agape, and Act 2 double-fisting vodka until I could coax it into closing. A ghost in the general shape of my corpse is currently writing this, fated to stalk the earth in crabby perpetuity until David Foster himself cuts me a check for some seance-based EDMR (I also accept Yamazaki, David, you unrepentant Saskatchewan sadist).

The next morning, I tried to locate CIA involvement in panicked peals of Googling, I poured over cast interviews, I searched in vain for an earlier version of the script—there had to be an explanation, right? A government psy-op, perhaps? A lost bet? A concatenation of traumatic brain injuries to all English speakers on staff? A curse from a particularly sequin-oriented witch?

Before I commence the yelling portion of this Substack, I’ll summarize the plot: BOOP! The Musical tracks the trials and tribulations of Depression-era cartoon character Betty Boop, specifically the Fleischer Studios version of Betty Boop, which lapsed into the public domain a number of years ago. Betty Boop lives, predictably, in a black-and-white world. She is famous in that world. She wishes she were not. She hops on her mad-scientist grandfather’s time-traveling couch in hopes of escaping the limelight and finding “something more”. When she arrives in the utopian future she’s so desperately craved , she lands at New York Comic-Con, is taken under wing by a teenage Betty Boop stan, falls in love with the teen’s trumpet-playing brother, and up-ends the mayoral campaign of a misogynistic waste management thug.

Then she goes home, and then the show ends.

Now, sure, the story is stupid, but stupidity is hardly an obstacle to good or likable musical theater—just look at Cats. Neither is nonsense, which festoons throughout BOOP’s treacly, haphazard book, penned by Drowsy Chaperone and Smash alumnus Bob Martin. The show’s culture-shock conceit is a time-honored classic that works well as a star vehicle for bubbly belter Jasmine Amy Rogers—her warm, winking portrayal of Betty Boop stands out as the production’s only real upside. The costumes pop, the stagecraft dazzles, some of the numbers even invite a timorous toe-tap or two, but none of these elements coalesce into a watchable product, much less a good idea.

That’s the issue—there’s an eerie hollow at the center of BOOP! The Musical, a deep, black hole where fucks should grow. I was perturbed far less by the show’s creative shortcomings than by its pointed insipidity; honestly, it’s sort of hard to rant in any amusing way about such a forgettable, asinine experience. I don’t remember the songs, the sight gags, or any of the minor character’s names. Instead, the most enduring takeaway I retained from the BOOP! experience was one of dread, haloed by a coarse, dark boredom that threatened to swallow me whole. BOOP! felt like the artistic equivalent of a dentist’s office waiting room, in other words, the antiseptic threat of a root canal included.

The show now sports its own meme, invented by the actress Hannah Solow. She made a TikTok inspired by an old man she overheard insisting in an antiquated Brooklyn accent, “We could see BOOP!”. It’s funny because Solow is funny, but also points to the heart of the problem—BOOP! is, at best, a second choice option, an alternative to better, harder-to-book plans (read: Oh, Mary! or Gypsy). (Rogers herself had to say the meme out loud on stage at some sort of ceremony recently, which feels like a concerted humiliation ritual, but I digress).

We could, indeed, see BOOP! Anyone with a couple hundred bucks could.

BOOP! isn’t a train wreck or an airball, reader. On the contrary, BOOP! represents far more culturally insidious forces— the end of fun under fascism, the ontological failure of froth as a fortification against apocalypse, and the rise of slop logic.

But first, a word about money.

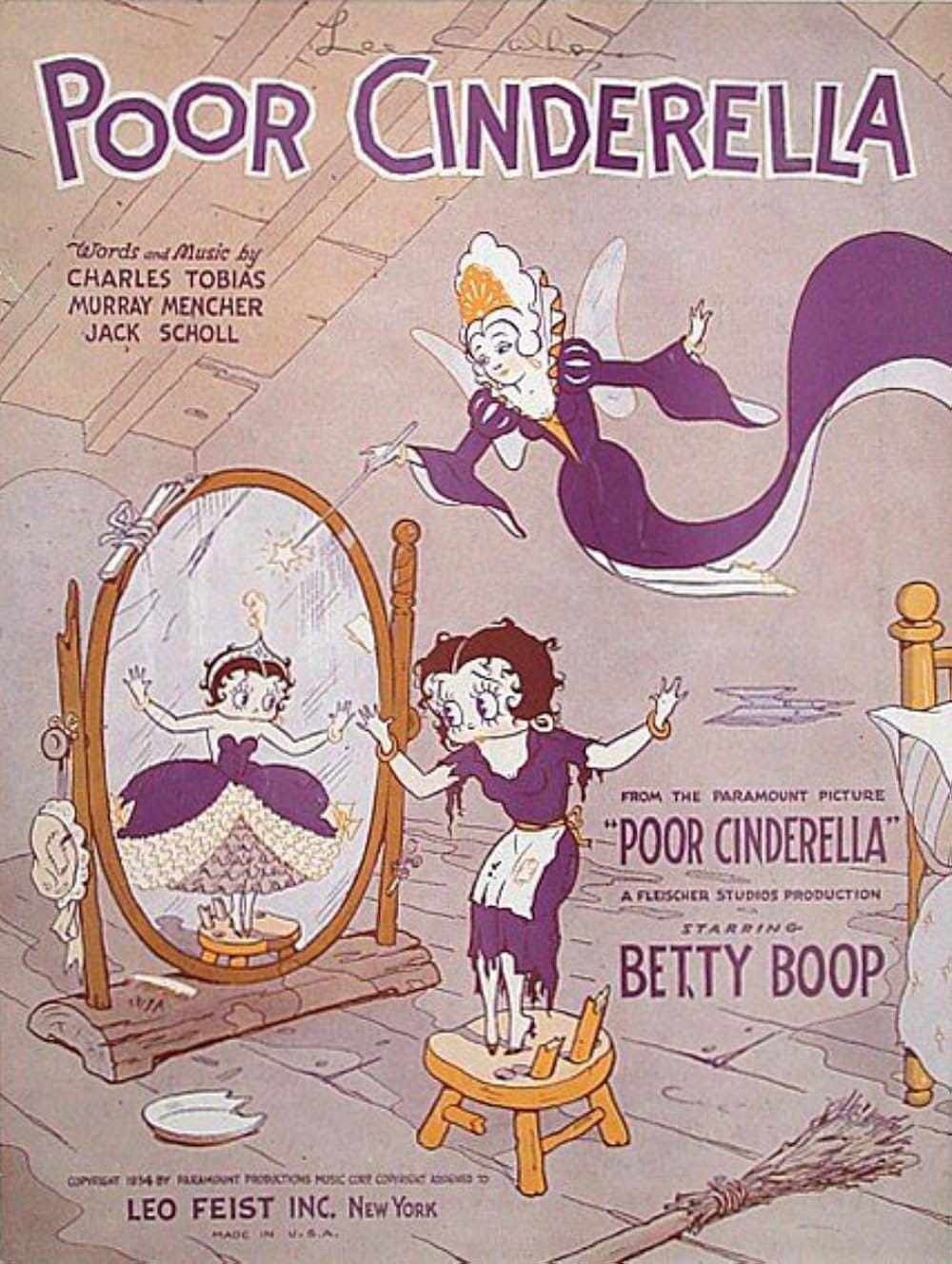

Part II. Poor Cinderella

In an article for The New York Times in May of 2025, Michael Paulson reported that Broadway has finally “bounced back” from the pandemic, at least on paper. The Broadway League, a theater owner’s trade organization, released data showing that the current theater season has grossed $1.801 billion so far, narrowly beating the $1.793 billion earned at the district’s peak in 2018. These numbers aren’t adjusted for inflation, however, nor do they reflect the 3% fall in attendance since theaters shuttered their doors en masse in 2020.

The League also offered two observations that trouble its optimistic “bounce back” narrative—”capitalization” costs, or Broadway production bills, have skyrocketed in the thousandth percentile over the last decade, and the biggest money-makers on Broadway aren’t actually musicals, but straight-forward plays helmed by film celebrities like George Clooney. With all these stats in mind, I feel twinge of guilt bitching about BOOP! —despite a warm reception from theater fans, the show has just announced an untimely closing date, necessary even in light of Rogers’ Tony nomination and the production’s sweep at the Drama Desk Awards. In a recent interview with Bloomberg Business’s Big Take Podcast, Tony-award winning producers Daryl Roth and Lucas Katler point out that the average Broadway musical takes $20 million to mount, attributing the hefty tab to sets, marketing, and union costs, which create a “prohibitive base level” of funding for the “80% of musicals that don’t recoup” on their investment. (Katler, in particular, drove home the “protections” of needy union workers as a primary source for this punishing overhead. It’s not. It’s rent. Bloomberg sucks).

This isn’t an unusual fate for musicals in a post-COVID ecosystem, where speculative spending and fickle fanbases have become the norm, but it is an illuminating one—BOOP! is the safest bet imaginable, pandering directly to what consumers say they want. A cursory nod to DEI in the form of a Black female lead who never mentions her race? Check! Original songs by the mega-composer who scored The Bodyguard? Check! Teen-friendly subject matter? Check!

Fucking tap dancing, I guess? Check!

BOOP! appears, at first glance, to be engineered for tourist season, promising multi-generational fun that won’t titillate youngsters or scandalize grandparents. It carefully refuses to update its sites of thematic provenance, specifically the 1980 version of 42nd Street, a David Merrick homage to Tin Pan Alley farces that ushered in a new era of big-budget Broadway revivals (1987’s Anything Goes starring gobby racist Patti Lupone springs to mind). I mention 42nd Street specifically because period musicals, like vampire movies, correlate directly with American economic uncertainty—the Great Depression gave us Show Boat, the stagflation of 1973 gave us A Little Night Music, the stock market crash of 1981 gave us Dreamgirls and Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, the housing crisis of 2008 gave us Billy Elliot and Spring Awakening. Even the terrorist attacks of 9/11 allowed Thoroughly Modern Millie and The Producers to become twenty-first century hits. The past moves units when the future runs out of wares.

The question of BOOP!’s two-factor failure at commerce and comedy isn’t a question of “how”, then, but “why”. It’s clear that its imbecility was purposeful—to what end?

But first, a word about nostalgia.

Part III. Don’t Cry For Me BOOP!-entina

The genesis of American musical theater was, ultimately, a function of economic infrastructure and escapism intersecting for the first time in a post-industrial context—the accessibility of operetta tickets to the working class coincided with the expansion of public transit and the development of electric street lamps, which meant girls with jobs felt safer staying out after dark. Regular people with regular lives wanted entertainment that wasn’t twelve hours long or sung in Italian. They yearned to get happy, to wipe all their cares away, to believe that they, too, could sing and dance their way to absolution.

While the social and intellectual import of the genre has ebbed, flowed, and shifted through the decades, musical theater has always embodied a certain individuated, liberal optimism, best captured by its tendency towards non-diegetic “hierarchy of expression”, a performance theory term that describes the form’s escalation of affect; when speaking no longer suffices, a character opts to sing instead. When one voice isn’t enough, a choir can assist. When voice alone can’t embody the ecstasy of self-pronouncement, dancing might take it place. Musicals prove so attractive to teens in large part because this affectual escalation is well suited to the shape of a Campbellian hero’s journey or literary Bildungsroman. This scaffolding also primes musical theater for the adoption of personal-as-political narratives, which limits much structural ability towards genuine artistic transgression. In the introduction to the fabulous 2004 PBS documentary series, “Broadway, The American Musical”, presenter Julie Andrews declares, “the Broadway Musical has always sung the promise of America”.

Now, don’t misunderstand me—artistic transgression is hardly necessary to tell a great story or have a nice time, nor is radical alignment a reliable or good-faith lens for criticizing popular culture. I’m not implying that all musicals need to be like, like Karl Marx biopics, nor that art must be pretentious and dour in order to be worthy of our collective cash or eyeballs. I don’t believe in “guilty pleasures” because I’m neither a Catholic nor an dullard; indulgence will always feature as a proud cornerstone of my personal praxis and credit card statements alike. BOOP! should have been a romp, an experience that evacuated my consciousness the moment I entered my Uber home, but instead, it stinks like second-hand hookah in the hem of my Fashion Nova Plus sweater, or mortal sin in the blood of my ancestors. I really cannot shake how fucking nonconsensual and haunting this particular perversion has proven to my spirit, reader. (Pass the Yamazaki, David).

In 2003, theater historian John Kerrick refuted accusations that musicals were “dead”, insisting that they were merely “changing” in tandem with the procession of time. “Will we ever return to the so-called 'golden age', with musicals at the center of popular culture? Probably not”, he said. “Public taste has undergone fundamental changes, and the commercial arts can only flow where the paying public allows”. And reader, change it has: the cultural role of musical theater reached the crest of its 21st century relevance with Hamilton, a project that explicitly served the hegemonic intentions of the state by absorbing Hip-Hop into its apparatus through the politics of representation.

This nominal acceptability of racial difference set the stage, so to speak, for Rogers’ Black Betty Boop, a sanctimonious nod to Esther Jones, the jazz singer whose mannerisms and personal style were stolen and white-washed in order to create the character Americans have lusted after for a century. Martin’s Betty, like Gerwig’s Barbie, is characterized as an upbeat boss babe revered for her “strength” and “ambition”, a laughable revision of both figures’ status as sexually exploited cyphers for consumerist desire. Betty’s objectification and harassment by strange, powerful men is played as a joke both in the 2025 musical and the 1925 antecedent it seeks to…subvert? Build upon? Reference? Like, what is that? Do I have to care about that as an audience member? Am I being encouraged not to? Is it funny to watch a Black woman get chased around a table by a lecherous white guy in a suit? It’s by far the most charming number in the show—is that on purpose?

Do we like this?

In the late ‘90s, Canadian theorist Linda Hutcheon wrote extensively about nostalgia and irony as flip-sides of the same coin, calling the two conditions “neighboring modes” of collective memory-making. “It is the very pastness of the past, its inaccessibility, that likely accounts for a large part of nostalgia’s power—for both conservatives and radicals alike”, she wrote in 2000. “Thanks to…technology, nostalgia no longer has to rely on individual memory or desire: it can be fed forever by quick access to an infinitely recyclable past”. What irony and nostalgia share, she emphasized, was an “unexpected twin evocation of both affect and agency—or, emotion and politics”. To Hutcheon, irony and nostalgia weren’t descriptions of a specific object or concept, but the shared articulation of response. Irony, therefore, did not exist in order to stave against the seduction of “memorial culture”, but operated instead as a post-modern “comment” on its power, a spotlight on the insistence of “complicity” in the “said and unsaid”.

If we accept that 2025 represents the crest of alt-right “post-ironic” internet culture, then, it follows that we have also entered a “post-nostalgia” moment, an algorithmic jumble of unincorporated symbols and signifiers that hang together in wretched symbiosis. Watching BOOP!, with its unfunny melange of dated Obama jokes, brazen allusions to iconographic IPs like Mean Girls, and muddled, near-Beckett-esque notions of personal liberation (in the final scene, Betty returns to an unfurnished black-and-silver stage and is joined, in a twist, by her earth-side trumpeting love, who has presumably been so crushed by late capitalism as a contemporary Jazz artist that he felt the need to swap one fascist depression for another—don’t fret, the political parallels are never mentioned, not even in passing) inspires not just the full-body incipience of sea-sickness, but a distinct impression that meaning, as we once knew it, is over. BOOP! trades yearning for yearning’s simulacrum, a Steyerlian “poor image” of a memory of what people used to like. It’s less than nothing—that’s the point.

If BOOP! purports to “get happy” at every turn, why did it feel so fucking threadbare? Why did we willingly sit through an onslaught of dumb punchlines about Times Square as the center of culture? More importantly…why were people laughing at these jokes? Why did BOOP! land so gently in the esteem of the theater-goers and critics? What the fuck happened, here?

The answer might seem unsatisfying, but still warrants some analysis, I think—the reason BOOP! flopped with such an existential ‘thud’ is because it adheres to slop logic, a permutation of the slop media machine. BOOP! was never designed to be a blockbuster; instead, it was birthed as a national tour horse with no internal architecture, edited by artificial intelligence ( I’ll get back to this accusation later) and marketed by heavily doctored Youtube clips of scenes that don’t reflect the plot. To even identify the show as a cash-grab is a disingenuous assignation, since the cash in question is being laundered in service of entirely different goals than stated by either the theater or the content itself.

When asked what he thought about jukebox musicals and the artistic arc of contemporary theater in a 2000 conversation with New York Magazine, , composer Stephen Sondheim decried the pervasion of “spectacles”, quipping, “It has nothing to do with theater at all. It has to do with seeing what is familiar”. BOOP! feels familiar, all right, in the same way ChatGPT might feel like a therapist, or Spotify might feel like a DJ, or TikTok might feel like a personal vibe curator. BOOP! scraped our data, figuratively at least, mining the residue of our most secret hopes and order histories in order to fabricate a product capable of stirring something close to satisfaction in a non-negligible demographic of paying customers. It’s not like anyone’s got enough money to attend the show twice, so why try to make something good? BOOP! proves itself unable to invoke irony or nostalgia, much less a dialectic between the two, and in doing so betrays a miserable truth—that cultural production, even the silly stuff, is happening to us, not for us, in 2025.

But first, a word about AI.

Slop In Real Life

Technologist Mike Pepi, whose book, Against Platforms, is very good, writes a lot about AI on his equally good Substack, Heavy Machinery. In a recent post, he railed against digital utopianism and its particular capitalist brand of doom-mongering. Digital utopians frame AI as an encroaching fog, rather than, as Pepi puts it, “just math”. Pepi argues that generative AI is neither a revolution nor an apocalyptic horseman, but something both more disgusting and banal—the inevitable result of start-up culture and it’s corner-cutting tendency towards fragmentation. He’s not alone in this opinion—online hot-takes abound identifying the culprit for generative AI’s mind-numbing, planet-nuking ubiquity as content culture itself, the pump-and-dump mill we have come to accept as a social constant. Viral TikTok noises, click-bait headlines, meme-ificiation, courier economic policy—together, these modalities articulate an edgeless arena for mass alienation. We’ve been trained to consume shit, so when shit slides faster down the chute, we unhinge our jaws out of habit regardless.

The phrase “slop media” was coined in order to describe the pestilence of “low quality” videos and images created by generative AI (think, like, a picture of Jesus made of shrimp on your grandmother’s Facebook feed), but I’d argue that expanding the definition of “slop media” to include the cultural output created according to AI philosophy, if not practice, is an essential to understanding our entertainment landscape. In an opinion piece penned last year for Polygon, Cass Marshall described slop as “content that is meant to be consumed, not examined, critiqued, or unpacked”, which is almost accurate—slop doesn’t resist dissection, it invites it. What slop nullifies is analysis, which is why reviewing Marvel movies (or BOOP!, for that matter) is such a fool’s errand. Slop encompasses more than just an LLM-voiced “Am I The Asshole” Reddit voiceover on a throw-away Instagram reel—the podcasts that litigate “Am I The Asshole” Reddit entries are also slop formations unto themselves.

I mentioned earlier that BOOP! didn’t make any sense, and I meant that shit. It’s not that the show was merely lazy or surreal– there was an almost dreamlike quality to its lunacy, as if I, as a viewer, was being rowed through the canals of Venice by a small dragon who spoke only Icelandic. I attribute some of this brainlessness to a quick-and-dirty edit and Bob Martin’s charmingly Canadian misunderstanding of New York boroughs, but it’s hard to ignore the plot-hole problems—if Betty Boop doesn’t know what colors are, why isn’t she bothered by iPhones, for instance? I’m hardly a stickler for cohesion, here, but without sense, it’s impossible to create stakes, and without stakes, it’s impossible to encourage the audience give a fleeting queef about anything happening on stage. BOOP! was constructed according to slop logic—whether or not generative A.I. was used to write or edit the content is immaterial. The results are the same.

BOOP!’s closure, slated for July 13th, (also the date of this Substack’s release, sorry about that) is being blamed on ‘weak ticket sales’, which feels a bit incomplete as an excuse—the show has been open three months, and was in the process of building a word-of-mouth cult following with audience members, mainly grown women, who allegedly warmed to it’s “joyful storytelling”. That word, “joyful”, appears in basically every piece of BOOP! press I can find. That’s the thing about slop media—you have to pay people to write about it, and the turn-around has to keep time with the marketing slush cycle, so PR plagiarism is encouraged instead of frowned upon. Like irony and nostalgia, joy could be accurately described as a reaction to stimuli—capable of urged through orchestration, but difficult to fake entirely. I’d argue that joy, while genuine, lives in the body as an affectual holdover for BOOP! viewers, an interior nod of recognition for older, more thoughtful antecedents.

Because I’m tiresome and, like you, am living through the violent collapse of the American empire, I can’t help but think about how crap like BOOP! is evidence of the Chomskian failure to articulate our evolving relationship to the privatized state apparatus. Our overlords no longer have to manufacture consent through the deft deployment of propaganda—instead, our leader waves his hand and systematically strips us of the protections that make being an American at all worthwhile in service of, what…private equity? Personal vendettas? 700 Club Jesus? Kids are being bombed and stolen and undereducated and overexposed in a media environment defined by the CEO of Netflix’s belief that his company’s greatest competition is sleep, for fuck’s sake. Everything is a sequel or a prequel or a remake or a redux in 2025 because new ideas are too interesting, a condition that might stave us against the epidemic levels of emotional abstraction we endure on a daily basis. I’m writing about BOOP! because writing about BOOP! is easier than writing about Alligator Alcatraz or Medicaid or I.C.E. or Iran, clearly, but I also think that BOOP! is evidence of a sweeping platforming impasse that allowed those atrocities to occur under our noses. Theater isn’t in crisis, but Broadway is. Cinema is not in crisis, but movies are. Entertainment, i.e., Nye’s notion of “soft power”, is America’s primary export outside of military surveillance. Media literacy isn’t at its nadir—media has been rendered so boring that literacy becomes either irrelevant or unwelcome. The process of grinding our synapses into paste is just another form of optimization, since attention and labor are now the same entity under an economic distraction model.

When Andrea Long Chu posited femaleness as a cultural alignment rather than an identity in her 2019 book of essays, liberal N+1 subscribers lost their fucking minds. I think we should apply the same tactic to BOOP!-ian joy. What if we re-frame Broadway’s “get happy” dictum as a threat? What if we refuse to feel the joy that we’ve been forced to lease from corporate enterprise? If I decline the opiate seduction of BOOP!, where does that get me, exactly? I could sharpen my dysregulation into a funny bit to make my friends laugh, but that just makes me feel cheap and un-heard, like a coal-mine canary being handed a bird-sized clown suit. I could write a 5,000 word Substack about it, but then I’m just re-directing the flow of all this poison into the shared belly of an audience I actually like.

Am I still talking? The show is closing, so didn’t I get what I wanted? Am I Broadway Morrissey, now? Just shoot me.

But first, a word about criticism.

What Even Is A Critic Anymore?

Jesse Green’s New York Times review of BOOP! is fucking hysterical. “Some shows are “what?” shows, leaving you baffled”, he writes. “Others are “how?” shows, as in: Dear God, how did that happen? But the most disappointing subgenre of musical, at least in terms of opportunity cost, is the “why?” show, a well-crafted, charmingly performed, highly professional production that nobody asked for”.

“BOOP! The Musical…is a “why?” show par excellence”.

That’s a phenomenal lede for a theater review, but the further I stray from my actual viewing of BOOP!, the more I disagree with Green’s premise, if not his appraisal of the product. BOOP! isn’t a “why?” musical at all. BOOP! exists because teenage girls buy Broadway tickets and Barbie blew up the box office two years ago. BOOP! exists because investors are risk-averse and contemporary cultural feminism has failed so spectacularly that it is now considered sexist to imply that romance novels are stupid or Death Becomes Her isn’t high art. Most cultural commentary I read rails against “anti-intellectualism” while insisting that activists don’t need to know any theory to organize effectively. Stating that Ocean Vuong is a bad writer, for instance, now constitutes a viral layup, since anything other than lavish praise or active bullying is considered exotic in the broader publishing sector.

In a 2021 book review, Orit Gat identifies the crux of the issue; “it’s not art criticism that is in crisis, but the world”. Shit is fucked up, and the algorithmic 24-hour news cycle won’t let us forget that it’s fucked up, so we crave the intervention of some kind of sense-making machine to shape an opinion out of chaotic scraps. Since billionaires own all the newspapers and each worthwhile journalist has moved to a paywall platform in order to do half-way decent work, this hyper-normalization project continues in the mass-conjecture of social media, where grievances and biases are swapped in for intellectual investigation at an ever-accelerating rate. The most successful contemporary “critics” are streamers like Anthony Fontana, a YouTube music critic with regional legacy radio experience who live-reacts to songs and whose “takes” can be distilled into bite-size TikTok clips. We yap at each other while our tax dollars underwrite genocide, we read a headline notification on our phones before declaring, eyes misty, throat thick with an anxious gulp, “we could go see BOOP!”.

Criticism reifies itself through calamity. I should know; I’m an art writer. Every two years, e-flux runs a bunch of opinion pieces on the death of art criticism and then Boris Groys hosts a bunch of panels about it and then Jerry Saltz opines about how critics no longer have impact on the market and then Divacorps says something snide and then Public Investigator has a meltdown about Zohran Mamdani and then the whole cycle starts again. In the case of theater, it appears Jesse Green’s post at The New York Times exists for the same reason that the institution of Broadway still does—the glamorous comfort of an era where writers were important and taste-makers could read. I, for one, think criticism is actually growing in the right direction, away from the smoke-filled cubicles of the financier-fathered Yale set, but I can’t help but notice that as diversity of voice and perspective grow more central to the practice in criticism (take, for instance, Nikole Hannah Jones and the triumph of her 1619 initiative), the field itself becomes devalued in the eyes of the public. When Charli XCX wore a baby tee emblazoned with the axiom “They don’t build statues of critics” and subsequently set the internet alight, I wondered why no one mentioned that…they do! They have! The critics lionized in stone are just…white men.

I get grumpy about Substack just like anybody else, mostly because it’s full of thin women worrying about Sabrina Carpenter and whether or not straight men view her as a person (I don’t think straight men know who she is, tbh), but I’m more saddened by the fact that so many incredibly talented and professionally experienced writers can’t get a bill-paying, health-insurance eligibility-leveling gig anywhere else. Further, taste arbitration, even the anarchic, un-edited, self-published kind I traffic in, seems to be no match for the BOOP!-esque regime under which we are coerced into functionality. It doesn’t matter if we hate the trash that Hollywood, Broadway, Netflix, Hulu, or Disney desposits into our front yards—they aren’t listening to us. They don’t have to.

So, who am I talking to? I believe in critique, still, and I believe in beauty, and I believe in writing until my fingers fall off in the hope that telling the truth is an ultimately noble exercise, but I don’t always know if this undertaking is emotionally honest or, dare I say, fun. Who needs censorship when you have American opinion glut, where words get lost in the sticky muck of surveillance sludge and McCarthyistic disappearing acts? So, who am I writing for? Myself? Perhaps that’s enough. If BOOP! refused to consider its audience, than I, too, can abandon my reader for self-serving ends. If BOOP! confused the aesthetics of pleasure for the lived experience of joy, then I, too, can attribute the expansive nature of freedom to the fleeting breeze of diversion. If BOOP! is permitted to exist, then I, in my selfish and terminally millennial imperfection, am allowed to write thousands of words in dissent of its culturally cataclysmic salience as a means of coping, if not transcendence.

Who can say, if I’ve been BOOP!ed for the better? Because I knew you, I have been BOOP!ed for good.

Thanks for reading! See you next month.

B