Oh, hello, there—

I. Olivia

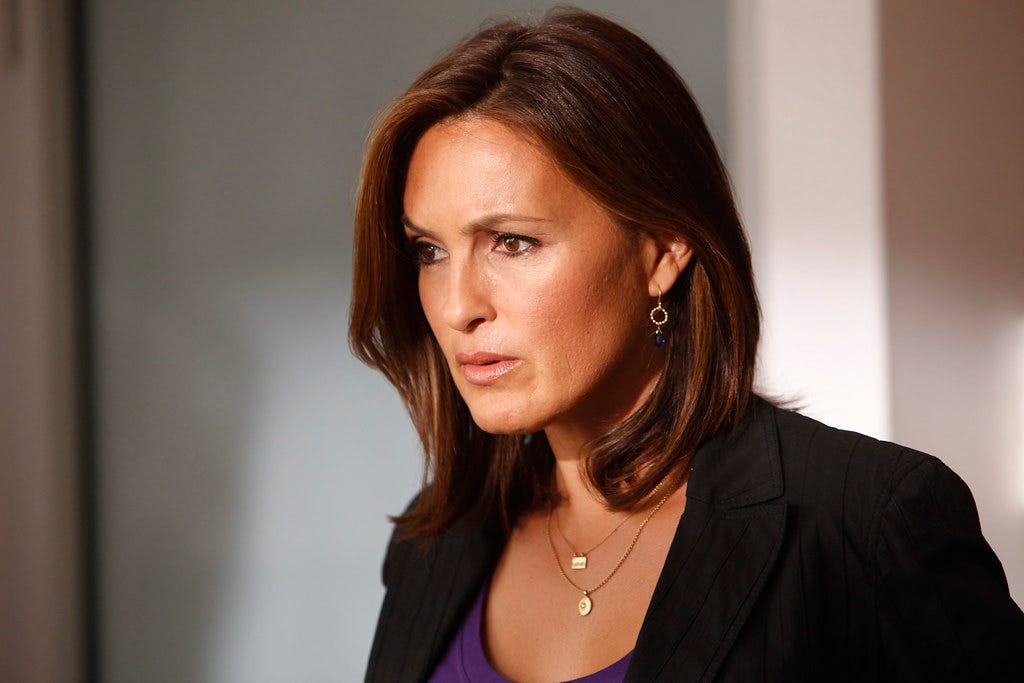

Detective Olivia Benson, brown eyes framed by a chocolate-butter balayage, knocks on a drab apartment door. The echo of her fist has been edited in post to obfuscate the film set’s emptiness —what looks like a pound sounds more like a shallow rap. A tight-faced woman wearing an inexpert lace-front cracks the threshold open, weeping.

“I told the other detectives I didn’t want to press charges”, she stammers.

“Give me five minutes”, Benson replies in a concerned, husky whisper. “If after that you want to stop, we’re done”.

I watch fragmented episodes of Law & Order: SVU on TikTok while I recover from some not-COVID-but-COVID-adjacent respiratory ailment, lying on my back and sucking on the disgusting lozenges my local urgent care prescribed. The minute-long, mirrored clips are scrambled, rarely sequential, but all communicate the same idea. Members of this elite squad, known as the Special Victims Unit, are consumed by the need to serve victims of the most sensitive, deviant, sanity-eroding crimes—rape, incest, human trafficking. “Special victims” represent the most painful ruptures in the collective imaginary of civil society; despite the almost mundane frequency of their violation , the bodies of these damaged people never inspire any statistical evaluation on human rights abuses or systemic iniquity in the SVU-niverse. Instead, “perps” and “victims” are both fetishized in the cyclical parlance of a 20th century freak show, ripe for seamless consumption in the telegenic marketplace.

Olivia Benson’s calling to the force feels tantamount to some saintly form of martyrdom, cannibalizing her daily life to the exclusion of boyfriends or hobbies or any semblance of routine. She is gorgeous, protective, fierce without sacrificing femininity. She never grows accustomed to the horrors of her job. Her brow is perpetually furrowed with solicitous agita, as if years of active listening has permanently frozen her facial muscles into an empathetic mask . The letter of the law is treated as a venerated inconvenience by Benson and her muscle-bound, hot-headed partner, Elliot Stabler, whose self-righteous aggression in the interrogation room transforms extrajudicial violence into wish-fulfillment choreography.

It’s not really a crime to hurt a pedophile, right?

Right?

Despite its gratuitous subject matter, SVU has been a a prime-time staple on American TV for over twenty years. This scripted program, oft-lampooned and regularly amused with its own campiness, (a tone that scholar Gillian Harkins calls a “contraction between sincerity and sensationalism”), is the only English-language procedural to be released in the 1990s that is still in regular production. 2024 marks its 26th season.

My now-deceased, socially conservative mother wouldn’t let me watch The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air as a tween, but had no problem turning on SVU reruns while she and I shared the kitchen loveseat after eating family dinner on week nights, mentions of semen or BDSM be damned. She loved Olivia, and these TikTok clips remind me of the way my her Tuscan meatloaf smelled, the aroma of secure, suburban predictability.

The truth is, my East Coast boomer parents didn’t consider SVU “inappropriate” for children because its narrative ethos was inherently Puritanical, (read: white supremacist). Olivia kept us safe from the poison of sexual ingress, from the grating chafe of difference, by glorifying the monied whiteness that distanced our family from her chaotic city sprawl. Olivia—clean, gentle, speaking in unmistakably Californian English to other members of the NYPD—embodies the ultimate neoliberal delusion—that the carceral state is women’s only defense against masculinity’s un-checked perversion, and by extension, Black subjecthood. To the self-sacrificing, hard-boiled Olivia, pleasure is, by definition, sinful.

According to this logic, SVU can persist for the same reason the police don’t have to be defunded —“rape culture” isn’t a structural problem, but manifests instead as an unfortunate by-product of the human condition. This shit will never end, so neither should SVU.

The woman in the bad wig has disappeared. In her place, a silver-haired man from an entirely different storyline stands in the middle of a city street, shrouded in thick, damp darkness. Benson screams at him with Shakespearean emphasis.

“As I said before, I won’t turn my back on any victim!”, she declares. “And if you stand in my way, you can take my shield and my gun!!”

Mariska Hargitay, the actress portraying Olivia Benson, blooms with moral beauty in this scene. The comments are filled with admiration from users of all ages.

“I love Olivia and KAMALA!!” one teen writes.

I sigh and scroll, only to be greeted with a slideshow of Kamala Harris, the former San Francisco District Attorney and Democratic Party nominee, grinning blankly in a variety of tailored suits , soundtracked by Charli xcx’s recent hit, “365”.

I sigh and scroll away.

II. America Has A Problem

In the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, media critics spilled a lot of ink on the subject of Olivia Benson’s ethical viability. Most of these essays followed the tried-and-true pattern of hand-wringing retroactive hit pieces, the most boring form of engagement with populist art. Jordan Calhoun penned an article for The Atlantic detailing his “break-up” with police procedurals, concluding that “Cop-centered narratives are unlikely to end, but my time with them has”. EJ Dickson opined in Rolling Stone, “No matter how much you love Olivia Benson, you have to be willing to grapple with the fact that she plays a major role in perpetuating the idea that cops are inherently trustworthy and heroic, and that many viewers are unable to distinguish between the gossamer fantasy of how justice should be handled, and how it actually is”. In 2022, Sarah Rebecca Kessler re-examined the allure of SVU in the context of abolitionism’s growing political popularity, concluding her essay with a recapitulation of the famed Angela Davis title, “are police procedurals obsolete?”. While most of these analyses managed to identify that lionizing police officers on film was somehow net-bad, few articulated exactly what about Law and Order: SVU proved so resonant with an increasingly left-leaning viewer base, a far thornier inquiry than their shrugging disavowal of “copaganda”.

The phrase “law and order” first came to American prominence during the 1968 presidential campaign of Alabama Democrat George Wallace, a man whose political legacy was cemented five years earlier during his gubernatorial inauguration speech in Montgomery, ground zero for anti-Black terrorism in the post-war South. “In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth”, he bellowed to a sea of white voters and news cameras, “I draw a line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say, segregation now, segregation tomorrow and segregation forever."

Later that same year, the Ku Klux Klan would bomb a Baptist church in Birmingham, claiming the lives of four little Black girls. Wallace’s speech had been written by a prominent Alabaman Klansman, a connection he would only disavow on his deathbed.

While his brazen racism ensured he would never hold national office, Wallace made quite the impression during his four attempts at the White House, transforming the vague verbiage of “law and order” into a militarized dog whistle. In a television interview during his 1968 run, Wallace responded to a hypothetical question about how he might “approach race riots” in his capacity as America’s new leader, “Well, to restore law and order, I’d provide moral support to the police, and also allow and encourage the police to install the law. The American people are tired of living without law and order”.

When Richard Nixon first addressed the nation as President just months after these remarks, he borrowed Wallace’s rhetoric. “Something has gone terribly wrong in America”, Nixon insisted. “The criminal does not discriminate. He strikes without regard to race or creed. And so when we call for Law and Order, we are calling for the protection of all of our citizens”. Nixon’s covertly white supremacist campaign leveraged this promise of “law and order” to broaden the Republican base, courting working-class white immigrants in northern cities by discrediting the Democrat’s comparative “softness” on rising urban crime rates.

In the wake of massive inflation, a series of failed foreign invasions, and a groundswell of progressive antagonism under Nixon’s giant nose, his successor, Ronald Reagan, spit-shined the party’s burgeoning “law and order” ideology into its own form of neoconservative pantomime, ushering in a litany of vindictive legislation that did nothing to address the criminal activities it was designed to curb. This was on purpose. In the context of the Reagan administration’s forestalling of AIDS healthcare, extra-curricular funding of the Contras at the outset of the crack epidemic, overhaul of equitable tax law, insistence on over-bloating national defense funds, and, of course, mass privitazation of higher education, “law and order” took on a near-genocidal timbre. Six months after his second term ended, the Law and Order series premiered to immediate fanfare on American TV. Nine years later, SVU would emerge on the scene in the thick of the mass incarceration-addled Clinton dynasty, eventually eclipsing its predecessor in popularity and staying power.

Numbers don’t lie—the folks stomping the streets to decry cop killings during the COVID-19 lockdowns of 2020 returned to their homes to binge episodes Law and Order: SVU on the same devices they used for sharing anti-cop infographics on Instagram. During the George Floyd protests, the hashtag “#ACABexceptforOliviaBenson” frequently trended on Twitter, implying that this cultural figment possessed her own unique vortex in the tornado of online revolution. Just two years later, Law and Order: SVU welcomed the return of Chris Meloni, reprising his role as Elliot Stabler for the first time since salary negotiations went sour in 2011. 2022 also bore witness to the resurrection of the initial Law and Order series, which went into syndication back in 2010. Today, proud owners of BLM bumper stickers and dashboard flags earnestly pray for the election of a lady cop to the ultimate seat of global power. Maybe she’ll call for a ceasefire in Palestine. Then again, maybe she won’t.

By now, most Americans have been forcibly acquainted with the cold, hard facts about contemporary policing, whether through first-hand experience or journalistic itemization. Even the well-worn “police brutality” euphemism serves to syntactically abstract the job from its experiential purpose. “Brutality” denotes a certain aberrative savagery, a rip in the fabric of otherwise upright community enterprise. A dictator could be described as “brutal”, but so could a dull Zoom meeting, or a long hike, or an unwelcome gap in reliable air conditioning. A more appropriate turn of phrase might be “state-sponsored execution”, or simply “murder'“. The New York Times prefers the first option.

So, we know that 98.1% of police killings in the last ten years have resulted in zero officer convictions, we know that 33% of police killings occur when the “suspect” is running away, we know that 69% of police killings happen in response to non-violent offenses or wellness checks, we know that Black people are three times more likely to be victims of police killings, we know that police academies enforce IQ caps on enrollees to discourage independent thought, we know that family violence rates are two to four times higher in law enforcement circles than in the general population, we know that the origins of the modern police state began with 16th century “Slave Patrols”, developed by plantation owners to terrorize kidnapped African workers into compliance—and that’s just the tip of the iceberg. If you’re Black or brown or trans or poor, you don’t need statistics to convince you that the cops are fascist agents of an oligarchic surveillance state; if you’re a white woman, you have, at very least, encountered the police as a particularly futile brand of non-assistance, a last-ditch escalation that rarely leads to any sort of straight-forward good.

Yet again, the numbers don’t lie — police precincts across the country have more government money, on average, than they did in 2019. Dystopian “Cop Cities” are regularly displacing local populations and corporate millions in blue and red states alike; The NYPD’s ever-expanding budget has not just eaten New York’s libraries and refugee services alive, but led to a series of mysterious satellite stations in foreign municipalities, including, of course, Tel Aviv, where members of elite squads like Olivia’s special victims unit learn “investigation techniques” from the trigger-happy IOF. It’s tempting to pretend that this trend reflects the untrammeled greed of our one per center overlords alone, but the truth is more deflating; Americans on every point of the political spectrum are voting in support of the police.

We fucking love cops.

III. Pussyhats

To fully comprehend the scope of Law and Order: SVU’s influence, it’s essential to take stock of the way carceral feminism subsumed what philosopher Sarah Ahmed termed the “affective economy” of #MeToo, an online movement that insisted on individual confession as the antidote to sexual violence five years before George Floyd’s murder rocked cyberspace.

In a 2022 interview with Angela Davis and her co-authors of the book Abolition. Feminism. Now! for the Boston Review titled “Why the Police Can’t End Gendered Violence”, BR staff writers get straight to the crux of the issue. “In almost all debates about police and prison abolition, someone will undoubtedly ask:What about the rapists?” the lede reads. If, like me, you’re a white woman who has endured some flavor of sexual assault, you know full well that this question comes up.

When I got roofied by a local bartender in 2021, I was shocked by how many self-described leftist friends of mine replied to my news with somber suggestions to contact the authorities. “I know it sucks, but you don’t want him doing it to another girl”, cooed one close confidante over text. I was disgusted, both by the inference that I was responsible for stopping this guy’s predation, and by the notion that I would ever, ever call the cops in a majority-Black neighborhood. From a utilitarian perspective, both my friend and I knew that nothing would be accomplished by filing a report. Best case scenario, I’d be questioned by a 23-year old Trump supporter while I screwed over a small business. I opted instead to call the owner and tell her what happened. She fired the guy. That seemed like enough of a consequence to me.

So…why did all these girls insist that I involve the police?

I relay this anecdote not on account of any outsized personal impact, but because it reveals an uncomfortable oversight in discussions of gendered abuse—most white women, even thoughtful ones, treat the police state as an inevitability. The cultural power of mainstream white feminism is derived from what scholar Alison Phipps calls the colonial “circuit between bourgeois white women’s tears and white men’s rage”, a performative, self-sustaining dialectic that strengthens the “intersecting violence of racial capitalism and heteropatriarchy”. The #MeToo movement, founded as a communal solidarity effort by Black organizers prior to its co-option by the Hollywood emotive journalism sector, leveraged “political whiteness” as its primary foothold to the exclusion of all other identities. Despite the glut of scholarship and above-board reporting proving otherwise, white women in the academy and beyond took umbrage with the perceived vagueness of abolitionist futurity. “ While “the community” might not be overtly abusive, “the community” plays a role in enabling domestic violence and is culpable for its ongoing existence”, wrote gender studies professor Dana Cuomo for Society + Space in 2020. “This presents a problem for abolitionism if it is to rely on “the community” as an alternative to criminal law enforcement”.

This weird, discursive ping-pong is a constant background noise in restorative justice circles, where white women readily admit that while the system is both erosive and incompetent, they can’t possibly imagine another option. Law professor and former DV prosecutor Leigh Goodmark, author of 2018’s “Decriminalizing Domestic Violence” and her explicitly abolitionist follow-up, 2024’s “Imperfect Victims”, has spent her literary career attempting to undo the damage she caused in her former profession. In an interview with the 19th Newsroom in 2023, she explained, “I started out as a pretty typical carceral feminist. I don’t use that as an insult. I use it as a descriptor. I believed, at the beginning of my career, that the way to deal with gender-based violence was to lock people up. Through study, through working with my clients who did not want their partners locked up and wanted other kinds of solutions, and through my work with incarcerated survivors, I’ve come to reject the idea that criminalization can solve these problems. It’s a violent system, and violence is not the answer to violence”.

When Twitter dunks on the Karen archetype, that lily-white poltergeist living to police Black joy, Black fun, her most craven attribute is often overlooked—Karen does not actually believe that the police will solve whatever problem her racism has concocted. She knows that real cops are pretty much useless. What Karen seeks in invoke is the Ur-Cop, the chasm between televisual justice and existential stress. She is summoning Olivia, a looming threat, a symbol of supremacist allegiance. What matters to a Karen is a cop’s participation in the theater of her victimhood, a performance she directs, writes, and produces in real time.

And that’s the thing—Americans don’t love Olivia because she represents the criminal justice system. They love her precisely because she doesn’t. She is the benevolent panopticon, the all-seeing centrist eye, a bonafide matriarchal dooms-daydream. More than merely aspirational, Olivia has been imbued by her audience with a mythic quality that only celebrity can engender—like Ellen Pompeo of Grey’s Anatomy, Mariska Hargitay, after a thwarted attempt at a film career, leaned into the role that made her famous rather than using it as a launching pad. In the wildest example of irony I have ever seen, she even produced and starred in a 2017 documentary, I Am Evidence, that drew attention to the US police system’s massive backlog of untested rape kits in storage facilities all over the country, quite literally shining a flood light on the gap between her role as a justice crusader and the real-world treatment of sexual assault victims. This bizarre display of hypocrisy made her even more beloved—Taylor Swift, author of carceral feminism’s most punishing anthems, even named one of her cats after Olivia Benson.

That brings me to Kamala. I wish it didn’t. I wish I was the sort of anarch-socialist who got a huge kick out of pissing off TikTok liberals or deflating the mis-begotten optimism of center-right moms who think a former Attorney General should be the mouthpiece for waning techno-hegemony. I want Kamala’s nomination to feel generative or refreshing, I want to believe that Tim Walz is my slightly cringey dad instead of an elected official. I want so badly to imagine that the folks clamoring for third-party defectors to vote Democrat think that Palestinian sovereignty is important. I’d love to share cute Kamala Brat memes smothered in a litany of blue heart emojis to my instagram. She smiles! She laughs! She speaks in full sentences! She cooks! She’s Black! She went to an HBCU! Project 2025 looms—who am I to bemoan the only option we have? Who am I to disappear into the comforting passivity of nihilism?

I scroll TikTok and watch a pretty young woman sputtering angrily into her phone. “All these leftists keep saying that when Kamala was a prosecutor, she was just locking people up left and right. It turns out she only locked up like, forty-five people? It’s all just bullshit propaganda!” I swipe away, only to be met with footage a well-coiffed gay man declaring that leftists are just as evangelical and extreme as the Christian right. Both speakers pronounce “leftist” with the disdain typically reserved for, well, pedophiles, as if leftists aren’t responsible for the few privileges we’ve managed to maintain as citizens. I marvel at how seamlessly the liberal messaging machine sows its intellectual concordance. I wonder how much money the Democratic lobby is saving at the expense of “creators” all over the privatized internet.

Forty-five people. That’s forty-five families, forty-five spouses, ninety parents, who knows how many kids. Kamala, in the spirit of Olivia, has spent her legal career, particularly in her capacity as the first person of color to be elected District Attorney of San Francisco, using the specter of intimate partner violence to justify the carceral process. She pushed for higher bail for criminal defendants involved in gun crimes, she cracked down on hate speech, and, of course, she criminalized truancy, putting the parents of kids who skipped public school, presumed to be pipelined gang members, behind bars. As Attorney General of California, she accepted donations from Steven Mnuchin before declining the authorization of a civil complaint against his bank. She voted to deny incarcerated trans women gender affirming care. Plus, her wrongful conviction case record leaves much to be desired, even by DC standards. Fascinatingly, in 2019, numerous journalists declared that her campaign’s characterization as a “progressive prosecutor”, a blistering oxymoron, lost her the Democratic nomination—the nation had “moved on”. In 2024, however, the American people welcome this CV not just with open arms, but with gleeful enthusiasm, only occasionally using the rhetoric of harm reduction to underscore the importance of her power position. That rhetoric, of course, implies that Joe Biden, arthritic architect of an unambiguous ethnic cleansing , has some kind of narcotic pull on the US populace, that the Democratic party itself shares an erosive epidemiology with fentanyl. Hauntingly, the metaphor works—both drown out the noise, sure, but too much of either powder will kill in due time.

Hope feels similar to me these days—glowing, synthetic, a short, cheap, hard-won high that distracts me from the dread vignetting my vision. I’ve been accused of being a Lee Edelman-type online, a champagne socialist (I prefer Tom Collins Trotskyist) who demands purity of a system I am protected from by privilege, and, honestly, that’s probably correct. When I see reels of Olivia Benson stills spliced with headshots of Kamala Harris on Instagram, I am not inflamed by some furious need to be right. I have no interest in dunking on anybody or explaining why this equivalency is a harbinger of evil. If anything, I’m enervated. I see the writing on the wall and feel insane. I watch footage of Sonya Massey being murdered by a cop, I watch TikTok users dog-pile the misogynoirist, bitter talking head who highlights the incongruity in electing a prosecutor to office in the wake of such cruel, obvious breach of humanity, I watch countless folks I respect and admire swear that we can vote our way out This, whatever This is, I watch limbless Palestinian kids beg for donations to pay off Cairo police at the Gazan border, I watch Charli xcx declare a cop “brat” after doing a bump of coke on camera.

I watch Olivia Benson, outfitted in tailored leather, place handcuffs on a D-list character actor, wincing for all that his Juliard training is worth.

“You’re under arrest”, she growls. “You’ll never be able to touch her again!”.

Before she reads the perp his Miranda rights, the image fades to black.

Thank you for reading. See you next month.

Subscribe, share, tell your friends!

xoxo

Baubo

Fantastic. I need a drink.

As always I love how you weave your thoughts together, a long march towards an obvious conclusion that sometimes I am reluctant to draw myself.