CW: Grief, again

If I were Jia Tolentino, I could write something tight and chewable about fetching my Dad’s ashes from the funeral home the day of a solar eclipse. I could write about the plangent, moody sun as it beamed grimly from the rear-view mirror of his Acura, or the inconsequential weight of his death certificates as they lay on the kitchen counter. I could craft an elegant little paragraph about missing him, or announce with calculated honesty all the ways in which I’m relieved he’s dead. I’m not Jia, though, nor am I Lauren or Sally or Amanda, and I really don’t want to talk about Dad, the trappings of losing Dad, the material considerations of Dad’s death.

Writing worked for me when Mom died. Writing does fuck-all for me, now.

Dad’s last words to me were, “Damn it, Torey, get over here”. Soon after, he slipped into complete unconsciousness, smothered in his own soil-brown, jiggling bile. I helped an aide cut his T-shirt off with kitchen scissors. I mopped phlegm from his beard and concave chest with a warm, wet hand-towel.

I’m back in Brooklyn after seven months in the suburbs of Massachusetts spent wiping Dad’s mouth and fixing his lunches. I remember wanting this, to come home, but my body doesn’t get it, yet. I impulse-purchased an orange lucite side table with Dad’s money for my apartment. My friends will hate it—everyone hates my taste in interior decor—and I will hate it too, probably. But it will help my house look less like his house. It will help build a third thing.

I’m quiet in my anger, perhaps because it doesn’t have a target, yet. I don’t feel missed, but I don’t particularly want to see any of the people who missed me insufficiently. I miss a version of myself that hardened into something I don’t recognize. Everyone loses their parents. I lost both of mine in a year. Isn’t that sufficient for missing? Sufficient for rage?

I’ve adopted Dad’s dog, George, who is curled up at the end of my bed and staring at me miserably as I type. He doesn’t understand the noise outside my window or why exactly he was brought to my two-bedroom in Bed Stuy. He doesn’t know that he lives here. I have no routine, no vague shape of a future to share with him.

Watch me as I adjust, yet again, to the trap-door reality I’ve fallen through. I’ll make another nest, I’ll smile hard and often, I’ll curb any urge to romanticize the sun. I’ll take George for a concrete walk and remember that he’ll never have to wonder whether or not he’s safe. I’ll keep going, I guess.

Where do people get the energy to start over? Grief has enervated me to the point of bleary resignation. An un-diluted, crystalline sadness is embedded somewhere down in the exhaustion, but I can’t stand to dig for it. I need to find new people, new purpose, but I mostly just want to sleep. I’m too disappointed to stay awake.

I’m waiting for some explosive surge of artful enterprise to save me. It’s nowhere to be fuckin’ found.

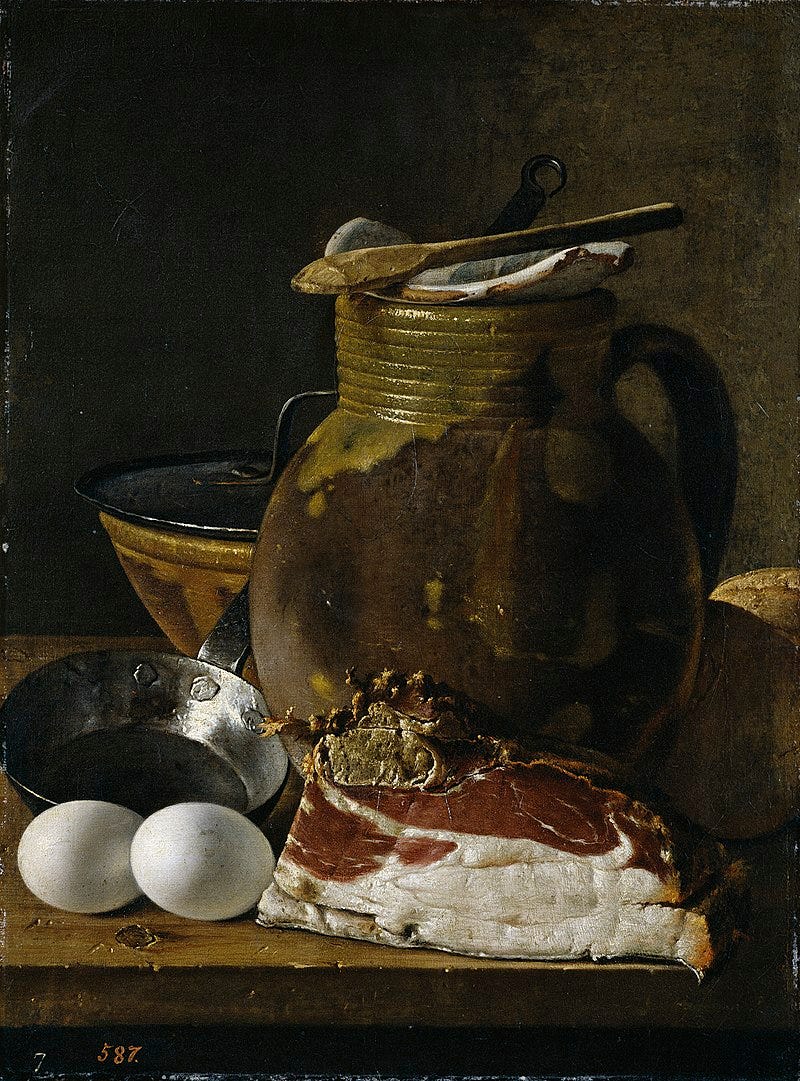

I’ve been thinking a lot about the painter Luis Melendez, now lauded as the greatest still-life artist of 18th century Spain. Dad liked his work quite a bit—stately, textural, sophisticated without sacrificing a certain masculine severity. In the mid-2000s, restorers discovered through X-ray imaging that almost all of Melendez’s canvases sported carefully rendered portraits on their first layers; between his hair-trigger temper and preposterously bad luck, he was never taken seriously as a court artist, only ever executing occasional commissions for Charles III without an official appointment of royal patronage.

As such, he was forced to repurpose his supplies, painting over perfectly good work in the hopes of making something that might catch the King’s eye. In the 1770s, still-life was the only genre that was regularly bought and sold on the open market, a god-send to artists who, for instance, had been expelled from Spain’s Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando for “inflammatory” quarreling. While Melendez died indigent with only a set of colored pencils to his name, his bold, sensitive explorations of Enlightenment-ready flora are lauded by historians as the finest examples of the Bodegon style, perhaps a shitty consolation prize for a life spent striving with no reward. Still, he never gave up. He kept pivoting. Instead of destroying his darlings, he used them as the foundation for better, stickier ideas. He stuck to his guns, and now we know his name.

Maybe it’s not inspiration or the sweet caffeine of creativity that will set us free.

Maybe it’s the capacity to remain stubborn in the face of heartbreak.

Thank you for reading and subscribing!

See you next month, hopefully with something cheerier to report.

-Baubo

I lost my dad and I hate it. Thanks for saying some true things I can relate to.

Thank you for this. My father is dying right now, and I relate to these feelings exactly about grief.