The first drink I ever legally ordered was a gin Martini, up, with olives. The fat-necked Boston bartender manning a sticky backroom I’d swanned my way inside seemed nonplussed, understandably so—this was a Jack & Coke spot, not a piano lounge patronized exclusively by the Rat Pack. I didn’t know that, because I was twenty-one and knew nothing. I’d watched my father order this cocktail a thousand times before, usually while donning a sport jacket in close proximity to some glistening ossobucco entree. Sometimes he’d smirk and insist on a “whisper” of Vermouth, going so far as to impress upon the waiter, who was also twenty-one and knew nothing, probably, that a classic Martini, an authentic Martini, a really, truly, bone-dry Martini, should be concocted via subtle, suave osmosis, or even better, alchemy—”Wave the vermouth near the glass, don’t pour it ", he’d instruct in a self-satisfied growl.

This was his ritual-within-a-ritual, a Boomer ballet I recognized as powerful. I memorized his choreography, but didn’t understand the dance.

When the bartender handed me the potion I requested, I felt like a grown-up. When I took a sip, I almost choked. It tasted like mop water cut with Ajax. I assumed some transformation would occur once cash changed hands across the hardwood, that I would come to appreciate the salty velvet of a shrub against my tongue, but baptism evaded me. I fucking hated olives. I still do.

I knew nothing, after all.

Martinis are hot right now, nostalgic metonyms for a time before the fangs of private equity sucked New York’s warm flesh cold. Recession-ready culinary aesthetics have always skewed pubescent, and now the twin brushes of inflation and Ozempic paint a nightlife world that smacks of bad A.I.—an epidemic of expensive baby food designed to be filmed, not finished. So too follows for the marketing of booze, an increasingly pricey and unpopular vice with Gen Z, leading to levels of crass mixological gimmickry that could make the Rizzler wince—the Tiramisu Martini, the devil’s egg Martini, the calamari Martini, the octopus Martini—chimeric monstrosities Frankensteined into existence by corporate hubris and the algorithmic flattening of personal taste.

In food critic Gary Shteyngart’s 2024 New Yorker romp, “A Martini Tour of New York City”, he positions the drink in its multi-various tacky iterations as a moat constructed to protect real New Yorkers from the siege of wellness culture. “Let the younger folks medicate with their Adderall to stay up and their benzos to come down. In the meantime, I would reach for my gin and my vermouth and one V-shaped glass to contain them all”, he opines. “I would dedicate myself to the cult of the Martini”.

There’s also gender trouble afoot—according to research from the University of Pittsburgh, women are outpacing men in both liquor sales and liver failure for the first time in recorded history. The manosphere’s backlash to third-wave social ingress may have resulted in a legislative windfall for woman-haters, but on the ground, patriarchal supremacy looks more and more like fun foreclosure than traditionalism— no dancing, no happy hour, no dozen oysters for the table, please, no 7 p.m. patio reservation with a trusted friend. Gone are the thin, pursed lips of suffrage-era temperance; these days, women must loose themselves, plumped with enough filler to stave their expressions against judgement.

I wonder what Dad would think of a Martini washed with cheese. I wonder what Dad would think if I told him Martinis weren’t actually named for the Italian liquor brand, but for the tiny town of Martinez, California, a San Francisco outpost best known for the bloody pestilence of gold rush opportunism. Fools sought gold and found vice in their sieves, cleaning pillaged rubble with the devil’s water.

I don’t have to wonder, actually. He’d tell me I was wrong.

You know nothing.

The Martini first reached mass appeal during Prohibition for such an American reason—the tipsy glee of good design. Martinez cocktails were traditionally served in curved coupe glasses, but in 1925, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts in Paris ushered in a new visual grammar for self-styled sophisticates in the form of Art Deco, re-imagining the coupe as a bold, angular flue with an extended handle that helped the liquid stay chilled and oxygenated at the same time. When the stock market crashed and the big, bloated rager of the previous decade trickled out, the Martini’s weathered glamour transformed into a winsome parody of itself, defined by its fictive kinship with the fictive Europe of ‘40s and ‘50s Hollywood, and now, Manhattan. My father’s impatience with heavy-handed vermouth vendors was actually borrowed from Winston Churchill, I’ve discovered. Reportedly, the bastard politician once quipped, “I would like to observe the vermouth from across the room while I drink my martini”. (Charming! Pity about the crimes).

It feels fitting that Martini mythos has oxidized in time with the valence of the modern gentleman, another bit of vernacular misinformation. The most enduring examples of Martinis in popular culture are both made-up and not technically Martinis—Ian Fleming’s cool, unflappable Bond, a symbol against waning empire, required his Vespers shaken, not stirred, insisting on both gin and vodka, so impervious was he to the girly debasement of intoxication. Ernest “fraid of nothing” Hemingway, the architect of taciturn 20th century masculinity, invented a ginny Gibson garnished with a single frozen onion (ew), a sadomasochistic disavowal of cocktail culture’s sybaritic upside—tasting good. Even the gentleman we associate most closely with the Martini, swinging crooner Frank Sinatra, was neither a gentleman nor a Martini fan—Ol’ Blue Eyes, a mobbed-up thug who fucked teenagers, preferred Jack Daniels (he was buried with a bottle in his casket).

“When did the Martini get so out of hand?” asked spirits expert Isabel Graham-Yooll in a May 2024 edition of her Whisky Weekly newsletter. “The Extra Dry Martini is now a perfect demonstration of a nested, metalevel, self-referencing performance. A drink that’s more about itself than about the moment”. I’d answer her simply; there is no Martini Ur-text, just like there is no primordial gentleman. When playwright Noël Coward declared that the perfect Martini “should be made by filling a glass with gin, then waving it in the general direction of Italy”, he missed the point. The drink was was a Yankee figment conjured up by a bartender named Jerry, a son of immigrants who ran a minstrel show out of the back of his saloon. Vermouth itself is a German liquor, albeit one that was popularized by the Carpano distilling dynasty in the 19th century. If you wave your gin in the direction of Italy, Italians will just assume, correctly, that you’re wasted.

Similarly, the notion of an American gentleman stems from a racist game of telephone. Derived from an Old French term describing the younger sons of title-starved nobles, gentil hom, today’s gentleman is based on Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s definitive ideal for the Antebellum South’s white planter class. “The power which the strong have over the weak, the employer over the employed, the educated over the unlettered, the experienced over the confiding, even the clever over the silly—the forbearing or inoffensive use of all this power or authority, or a total abstinence from it when the case admits it, will show the gentleman in a plain light”, wrote Lee, laying bare the foundations of U.S. noblesse oblige. All men kill; gentleman kill correctly.

Nightlife journalist and flapper extraordinaire, Lois Long, who put the emergent New Yorker magazine on the map with her irreverent Lipstick column, believed Prohibition wouldn’t have been a necessity if men could have “learned to drink with aplomb”. “We will teach the young to drink”, she posited. “There would not be so many embarrassing incidents of young men falling asleep under the nearest potted palm or playing ping-pong with Ming china if little Johnny at the age of six, had been kept in regularly at recess to make up his work because he had failed to manage his pint in Scotch class…”

If the Martini features heavily in our collective mirage of good white men, the semiotics start to shift when women enter frame. In her 2014 article Portraying the Alcoholic: Images of Intoxication and Addiction in American Alcoholism Movies, 1931–1962, Australian sociologist Robin Room pointed out that the consumption of liquor onscreen typically signals a fall from grace for female subjects. “For women, drinking went with sexuality, but for men, it replaced it”. Film history may be thin on girl comic drunks, but it is lousy with lascivious, bitchy breakdowns. The image of a Martini in the hand of a leading lady has historically denoted the dissolution of a family system, the unraveling of feminine social mores, or, scariest of all, the harrowing specter of middle age. Filmic masculinity reifies itself through rejection of vice’s undertow—heroes hold their liquor, heroes go home on time. They needn’t abstain because abstinence implies a lack of self-control. Bad girls, wild women, banshees, on the other hand, are incapable of resisting sin. They are transformed by it, poisoned in its presence, unable to attach the apple back to its broken branch.

As is common in cases like these, it’s important to blame both patriarchy and the U.S. government (same difference).

1920s Hollywood had a problem—A-listers kept murdering and raping each other with impunity, and scandal-logged president Warren G. Harding faced mounting pressure from religious organizations and state legislatures to pass sweeping federal decency laws to combat social decay, especially in light of Prohibition’s glaring failure to curb saloon culture or keep flappers from flapping. After a series of warnings, Hollywood opted for self-censorship instead, tapping Republican Presbyterian elder Will H. Hays to rehabilitate the industry’s image. Hays created “the formula”, a set of moral edicts that studios were encouraged to treat as scripture. In 1927, “the formula” begat “the Magna Carta”, which eventually turned into “the code”, developed from a submitted list of standards written by concerned Catholic layman Martin Quigley. The Hays Code resulted in a lot of stupid nonsense—no adultery, no kisses that last more than three seconds, no happy homosexuals, no on-screen deaths, no social realism.

The Hays Code instructions about drinking were pretty straightforward. “Drinking must be reduced to the absolute minimum essential for proper plot motivation”, read the second amendment to the Code’s “general principles” section of 1930. “What is objected to is the incessant “smart” drinking apart from any story demands, or the exaggerated use of drinking for comedy purposes”.

On a movie set, the last shot of the day is called a “Martini shot”. A hard-won treat, an end in sight. One for my baby, and two more for the road.

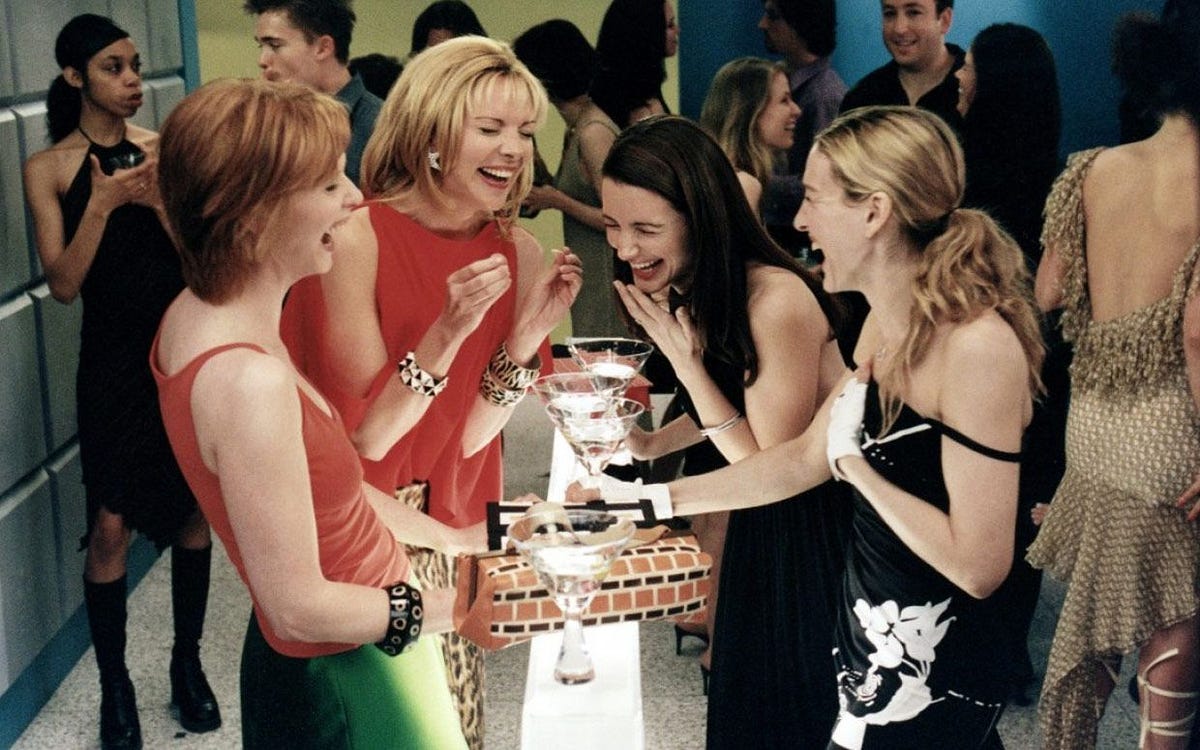

The recent Sex and the City revival on TikTok tends towards cross examination, an attempt by the PR girlina set to identify where It All Went Wrong, but it also serves as a reminder of the show’s impact on women’s drinking culture. Carrie Bradshaw inspired the Cosmopolitan boom, a Martini-shaped, slammable cocktail that seduces customers into a stupor with its pretty pink hue. The girls rarely had hangovers, seldom threw up in the back of cabs, and never seemed to call out of work. In the realm of SATC, pre-diabetes, sexual assault, sick parents, and 12-step meetings were non-entities—for the post-feminist handmaidens of the dot com boom, the vodka flowed in tandem with the stock market. Men came and went. They didn’t have to talk about their jobs because their jobs were guaranteed. Miranda’s sloppily written alcoholism in the show’s limping revival, And Just Like That, plays like an austerity-era apology for the perimenopausal flapper, a twinkling threat to the relevance of family values. Sex and the City helped re-frame the Martini as a signal of new, urban womanhood, of bubbly hegemony, rather than Kitchen Sink decay.

The popularity of the West Village-coded espresso Martini in 2025 is due, in part, to the resurrection of Thatcherian psychogenesis—a British bartender pioneered the drink in 1983 to mimic the effects of cocaine. (Didn’t NY Mag say the ‘80s were back? I don’t read that shit, so I don’t know). Our New Woman feeds on New York kitsch, relegated to the status of consumer over citizen.

Soon, Martinis will fall out of fashion again, an essential segment of the cycle that renders them romantic. It occurs to me that I have spent much of my 30s sitting at beautiful bars with my friends, opening our throats like baby birds against the edges of sweating stemware. It occurs to me that I write about love on a Macbook I refuse to back up on an external hard-drive. None of this feels particularly fun or cool. We don’t talk about men together, anyway. We talk about the end.

That’s the thing about Martinis—you drink them to remember and you drink them to forget.

Leftist author Malcolm Harris describes America as a series of popped credit bubbles—Dust Bowl, Stock Trade, Company Town, Gold Standard, Housing Market, the list goes on. My financier father died, and then my country fell to a technofascist coup that I sincerely wish could be considered partisan. Trump started a shot clock on time that was already borrowed.

What did Henry James say? That being an American was a “complex fate”?

What is my balance? Whom do I owe? Are the wages flesh or data? Is there a difference?

Show me, and I promise I’ll settle my tab.

The last Martini I ever fixed my father was Limoncello-infused, as was his preference. In protest, he had poured my first attempt on the rug beneath his Barkalounger, which cigar smoke had turned the same color as his pinched, jaundiced skin. In his defense, I had done a shoddy job, on purpose, maybe. The Prozac prevented him from screaming at me most of the time, but the stage 4 cancer hardening his belly and strangling his guts did not inspire kindness. He couldn’t stand without a walker, so I had to remake his order.

I didn’t want to. I was so, so tired of doing things I didn’t want to do. Hospice is hard on an oldest daughter.

God, do I set a scene, here? Or do I pivot and lionize him, instead? That’s my impulse. Why don’t I tell you about the moment he discovered the Limoncello Martini during our much-canonized vacation to Tuscany when I was 12? I only remember through his telling, but I can lie, right? I can wave in the general direction of Italy.

Never mind. I’ll keep the details to myself.

I can’t write beautifully about my Dad. I hope to, someday. He was an elegant, interesting man with a fast brain and a faster temper, the closest thing to a gentleman that has ever or will ever exist.

I loved him. I think he loved me. I miss him and I’m glad he didn’t have to watch Elon Musk wobble around the White House on TV. I take good care of his dog, George, and I cling to the tender moments of closure we achieved in the seven months I acted as his caretaker. I am angry, still. I look forward to a future where I am not.

Dad loved Frank Sinatra, specifically the bombastic big band stuff that cemented his legacy in the ‘50s. I prefer his later easy listening albums, the ones critics found depressing, that showcase his once-virile, worn leather baritone.

The time is right, your perfume fills my head, the stars get red, and oh, the night is so blue

And then I go and spoil it all by saying something stupid like I love you

I love you

I love you

I love you

Worth its wait in gold 💙✨