When? What? Why? for October 7th

Hmm, this is making no sense to the average listener... Let me try to explain myself in a few words

-CMAT, The Jamie Oliver Petrol Station

I. When?

In August, I visited Amsterdam alone. I loved the city both because it was explicitly designed for American ease—the Dutch invented market capitalism, after all—and also because I covet solitude with the relish of a vintage-sniffing sommelier. I wandered, I ate, I snapped photos, I spoke seldom, I read four books in as many days, I refused to consume American news.

I spent hours at the Stedeilijk Museum, a mere snert’s toss from the Netherlands’ embattled shrine to Vincent Van Gogh. It was the only tourist-forward institution I encountered on my trip that mentioned the Dutch East India Company’s atrocities in Suriname or Indonesia, albeit in passing.

It also housed a large collection of W.E.B. Du Bois’ infographics. I had never seen them in person before.

As a Black man who came of age in the thick of Jim Crow terrorism, Du Bois knew how to read a room. It was 1900, and the world was spinning fast—break-neck industrialization soaked the global moment in blood. Black Americans had paid for their freedom with conditional personhood. A World War brewed in Europe, eugenicist science had roiled into the mainstream, and Du Bois, a brilliant, stubborn man who believed in talent as a conduit to liberation, identified a weird new way to parse the chaos—data visualization.

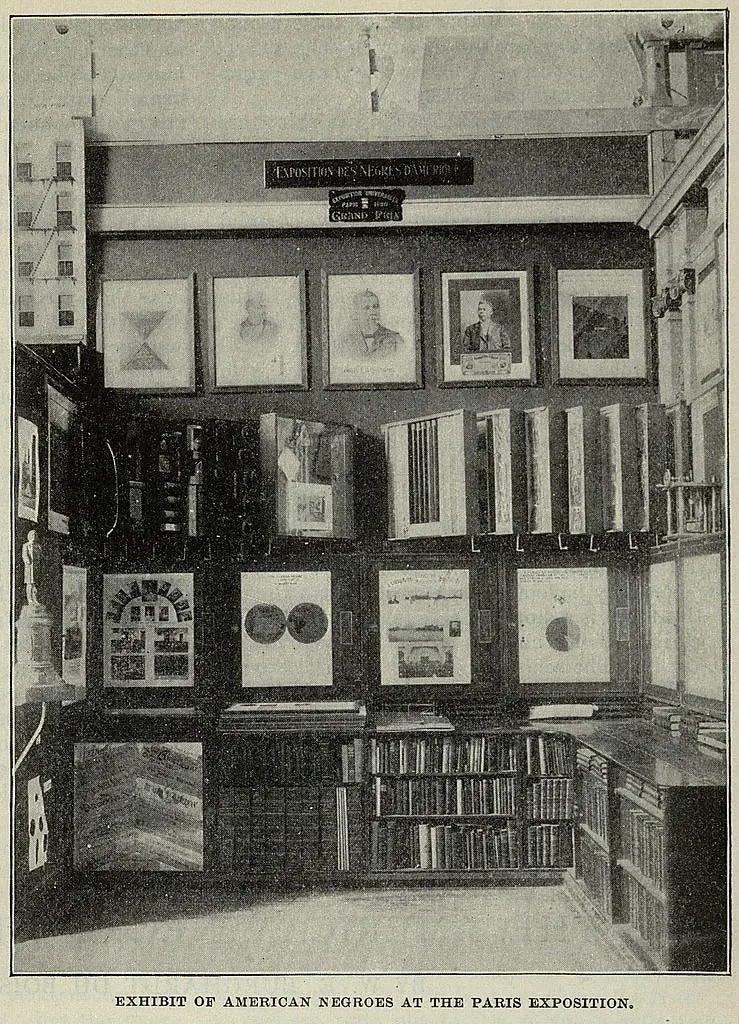

In 1897, the same year the notion of “separate-but-equal” was enshrined in law by the Supreme Court, Du Bois launched America’s inaugural sociology program at Atlanta University. He had spent his tenure as Harvard’s first Black doctoral student conducting a sprawling ethnography of African American life in Philadelphia, catching the eye of former classmate Thomas Junius Calloway, a lawyer and journalist who had recently petitioned the U.S. government for a Black-sponsored space at the upcoming World’s Fair in Paris. When the feds appointed Calloway a special agent in 1899, he knew exactly who to call—Du Bois, a fellow upstanding gentleman of letters who could help him articulate Black excellence to a European audience. Together, they embarked on a watershed exposition, “The Exhibit of American Negroes”, a collection of more than 500 photographs tracking the triumphs of the African American diaspora, carefully curated to buck stereotypes and warm the cold, punishing shadow slavery still cast.

Du Bois wasn’t convinced of the show’s impact, however, fearing that pictures alone might flatten its purported message. “It is not one problem”, he wrote, “but rather a plexus of social problems, some new, some old, some simple, some complex; and these problems have their one bond of unity in the act that they group themselves above those Africans whom two centuries of slave-trading brought into the land.”

After convincing Congress to pony up $15,000 just four months before opening day, Du Bois contracted a fleet of interdisciplinary field researchers and graduate assistants, armed them with buckets of gouache, and tasked them with a project that would portend the future of Modernist aesthetics. 63 graphic statistical transmogrifications in peals of blaring, bright geometry swung from vertical vitrines in the Exposition Universelle booth, hung proudly beside patents, books, and myriad other evidentiary slices of Black American life, organized with an archivist’s flair for sophistication.

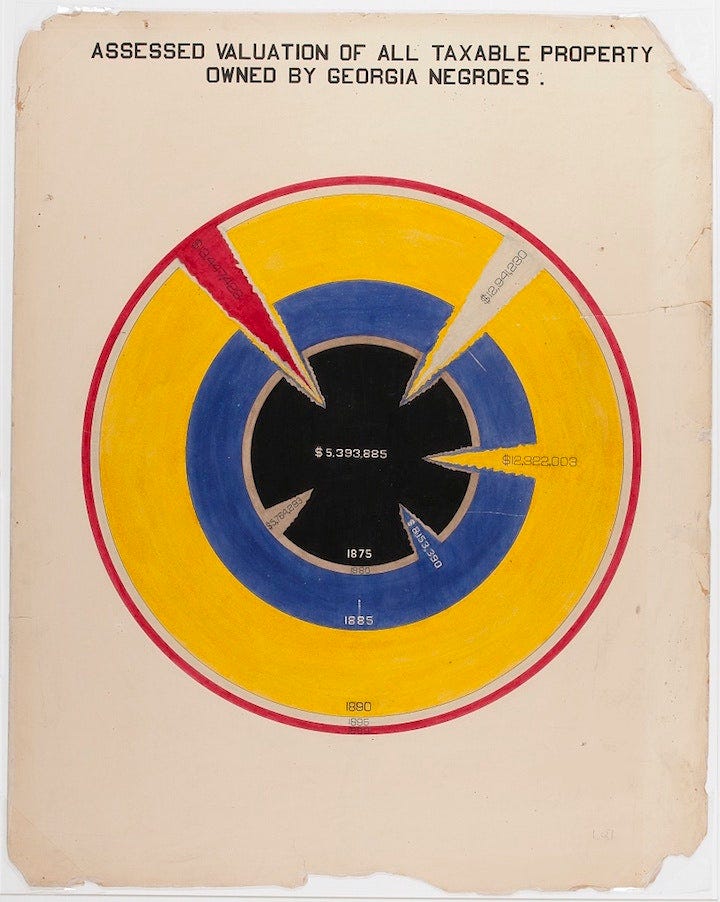

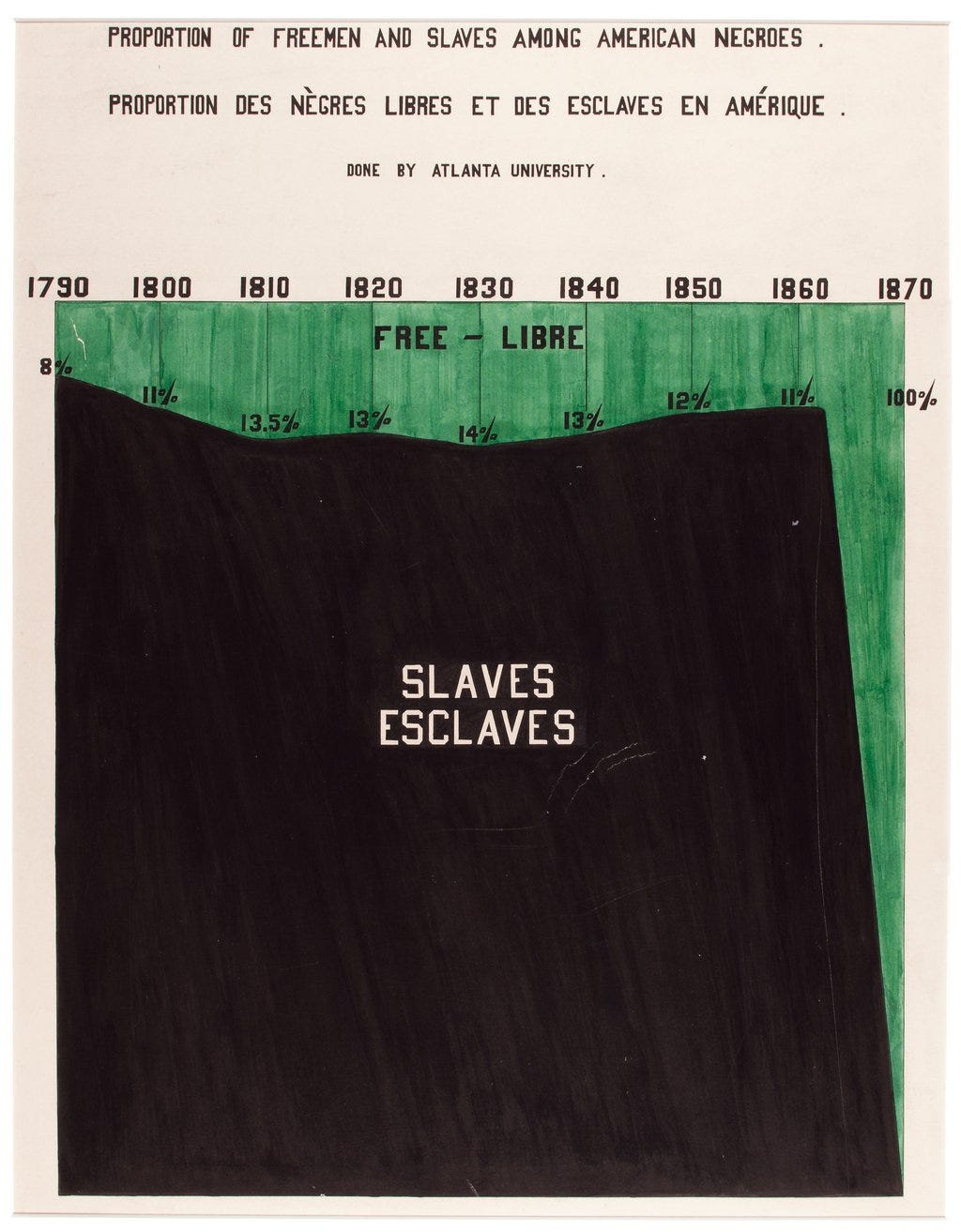

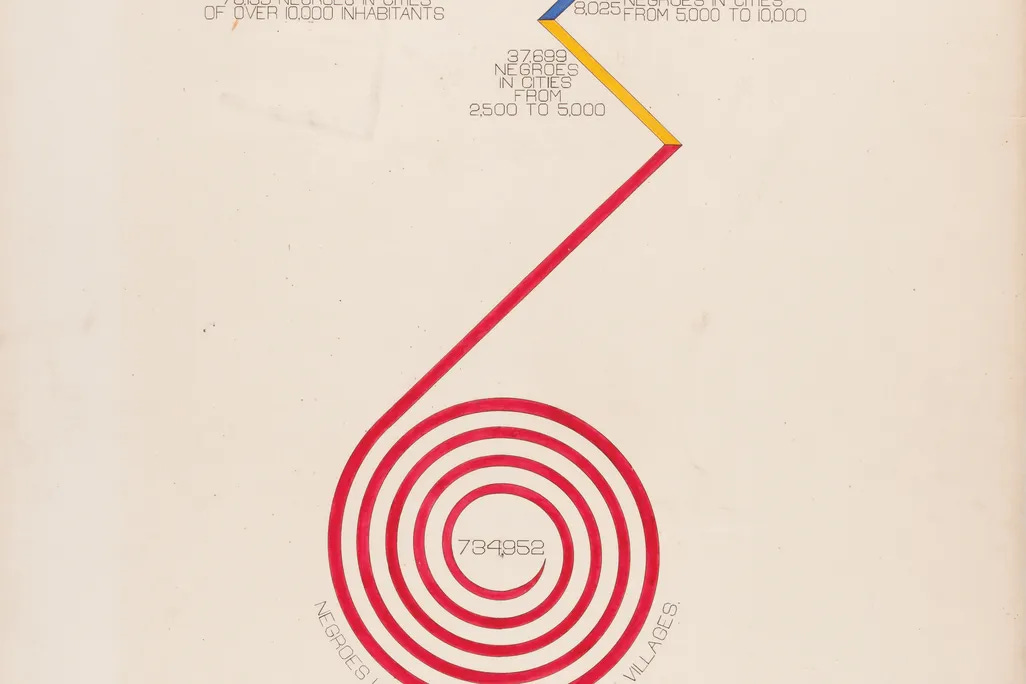

The charts reflected two distinct datasets. The first, The Georgia Negro: A Sociological Study, highlighted the lived experience of the country’s largest Black population. The second, titled A Series of Statistical Charts Illustrating the Condition of the Descendants of Former Slaves Now in Residence in the United States of America, broadened that scope to the national level, delineating spatial distributions, gender breakdowns, and even the blunt horrors of the middle passage in its pages. Both drew inspiration from a particularly stylish series of 1898 Census visualizations, The Statistical Atlas of the United States, responsible for depicting the foreclosure of the American frontier as “manifest destiny” dwindled into ecological disaster. Du Bois’ designs diverged from the Atlas in a decidedly Cubist direction; not only did his graphics reflect a radical de-centering of white supremacist metrics, but their compositional swagger predicted the spidery abstraction of Kandinsky, Matisse, and Picasso. His virtuosic eye for graphics even garnered him a signature motif—the “Du Boisian Spiral”.

Major media outlets didn’t acknowledge “The Exhibit”; aside from some mentions in Black newspapers, Du Bois’ efforts were largely ignored. His attempts at a new epistemological pluralism, distinct in its optimistic vision for Black futurity, had arrived years before its time, a burden Du Bois would bear at various points throughout his career. The “Du Boisian” spiral was more than a design feature, then—it was an optical metaphor for the Sisyphean problem of Black originality.

In Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois famously theorized “the veil”, a metaphorical barrier barring white racists from comprehending Black people as fully human, leading to “double-consciousness”, a plight in which Black people see themselves through the tandem prisms of the oppressor and their own experience. It’s not difficult to locate the seed of this concept in the presentational helix of Du Bois’ knowing—a curvaceous Trojan Horse for all-but-futile respect.

These “data portraits”, now framed frankly in a small, foreign room, were only digitized by the Library of Congress in 2014. One book has been released about them, I think.

I wish they could all live together in America. I know why they can’t.

Du Bois’ penchant for the color red stands out in this series. So many of the images, stark, loud, fashionable without precluding fury, resist an urge to bleed. The work feels urgent. Their materiality reveals the stakes of their creation—brush marks betray a time crunch, mottled paper edges speak to shoddy storage practices. Du Bois’ vermillion flourishes remind us that these numbers are mortal, describing unspeakable grit in the face of preposterous, state-sponsored odds.

“Odds” is a euphemism, of course. “Odds” means death, depravity, corporeal horror, psychosis, destitution, torture, despair. “Odds” means fractured faith. “Odds” means something even crueler than an absent God.

At which bend does a spiral become a bullseye?

In his 1940 autobiography Dusk of Dawn, Du Bois described the “red ray which could not be ignored”, the systemic racism that undercut his sober studies as a social scientist. “I was going to study the facts, any and all facts, concerning the American Negro and his plight, and by measurement and comparison and research, work up to any valid generalization which I could”, declared Du Bois of his time at Atlanta University, outlining his fighting logic—if he could just get white people to understand the math, the what, to locate empathy in the personless world of his charts, he’d have a shot at advancing the fate of his people.

On April 23, 1899, a Black man named Sam Hose was lynched, accused of killing his landlord’s wife. Armed with a smart, careful essay on the subject, Du Bois marched downtown to the Atlanta Constitution newspaper office, firm in his belief that he could persuade readers of Hose’s humanity if they just read his statistical analysis. As he walked from the University to the Constitution’s doors, he heard the news—Hose’s body had been dismembered and displayed in a local storefront he’d be likely to pass on his route.

Du Bois’ stomach churned. He ran home and locked his draft in a drawer.

“Two considerations thereafter broke in upon my work and eventually disrupted it”, Du Bois reflected on this moment. “First, one could not be a calm, cool, and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched, murdered, and starved; and secondly, there was no such definite demand for scientific work of the sort that I was doing. I regarded it as axiomatic that the world wanted to learn the truth and if the truth was sought with even approximate accuracy and painstaking devotion, the world would gladly support the effort.”

Du Bois did not consider his under-sung designs failures of communication. He knew that the racist establishment class wouldn’t care; he prepared for that. He also prepared for the fact that his “data portraits” were never returned to him by the Library of Congress. They would not be presented to the public again in his lifetime.

A meticulous, calculated man who ate dinner at 5 pm on the dot every evening, Du Bois got good at weaving despair into the chain mail of his intellectual program. He started his career railing against the “Great Disappointment” that Reconstruction imbued in Black Americans, the foundational betrayal that he would later come to understand as a part of a larger imperial undertaking by the white “West”. (Du Bois abandoned his “talented tenth” platform after WWII, transforming into an avowed (and hunted) socialist. His 1951 McCarthy trial was only dismissed because Albert Einstein agreed to act as his character witness. When the United States government returned Du Bois’ passport in 1960, he promptly moved to Ghana.)

In other words, he bent that red ray, that slicing, neon roar of violence, into a target’s coil, inviting the world to gaze hard into the center of his ire. Du Bois burned his hands, his heart, so we could learn at his expense.

As I pored over the careful mark-making in Du Bois’ visualizations, I returned over and over again to his phrasing—he described them as ”data portraits”. There’s an unexpected tenderness to that term, an acknowledgement of the personal stories undergirding his science. Du Bois’ research revealed statistics on marriage, home ownership, employment—the most mundane, which is to say the most intimate imprints of self that anyone can name.

Perhaps a cheap literary analogy with today’s Instagram infographics, those meager, millennial-salmon slideshows instructing well-meaning dopamine addicts how to “build community” in their gentrified neighborhoods without being tap-traced by the feds or donate to displaced Gazans without being bank-traced by the feds or protest without being bio-traced by the feds or ask useful questions in Spanish of ICE prisoners being disappeared in Walmart parking lots without getting phone-traced by the feds, falls short of W.E.B.’s memory, here. Perhaps it’s too stupid, or too sloppy. Still, I can’t help but encounter the internet these days as a desperate, tangled snarl of directions from nervous people attempting to look and feel less nervous for hoards of other nervous onlookers. A.I. spits out listicles at such an outsized rate because it operates in averages—people seek out itemization, so itemization reigns king.

We want to be told what to do. Does anyone know what to do?

I think Du Bois knew what to do. Someone should have listened to him.

II. What?

I’m still not explaining myself very well at all Let me try, let me try again, let me try

-CMAT, Jamie Oliver Petrol Station

In 2023, Notre Dame English professor Sara Marcus released a book called Political Disappointment: A Cultural History from Reconstruction to the AIDS Crisis, that characterized the progressivist propulsion of American politics (read: Black organizing) as the suffusion of “untimely desire” into the broader cultural ecosystem, defining “political disappointment” as “a longing for fundamental change that outlasts a historical moment when it might have been fulfilled”. Instead of framing America’s self-perpetuating mythos as a linear whack-a-mole of problems, protests, and solutions, Marcus argues that disappointment is a useful engine of change, that is shouldn’t be side-stepped or avoided in political praxis. Failure, she writes, is a product of finality—desire’s continuity promises the perpetual, the never-ending strive towards betterment. Marcus quotes Du Bois’ introduction to Souls of Black Folk— “The Nation has not yet found peace from its sins; the freedman has not yet found in freedom his promised land. Whatever of good may have come in these years of change, the shadow of a deep disappointment rests upon the Negro people—a disappointment all the more bitter because the unattained ideal was unbounded save by the simple ignorance of a lowly people.”

What would Du Bois say about the optimistic energy of the Black Lives Matter era devolving into a second Cold War? How would he opine about TikTok-ing heads online telling us to vote or not vote or shoot or not shoot or log off or log on or speak out or shut up?

What color is his spiral in 2025? Sea-foam green for the disappearing reefs? Orange for groyper sub-Reddit supremacy? Midnight Black for fucking Palantir? Maybe he’d create a braid of floating vectors in the shades of the Palestinian flag, carefully illustrating to yet another generation of closed-ears, open-mouthed idiots the proportions of the moral debt America owes.

If we consider disappointment a type of kindling for change, a non-colonial process rather than a fixed position, how can be theorize despair? There’s been some good pro-despair writing since Trump got re-elected and started his shock-and-awe return to the ‘80s social milieu in which he was first relevant—luminary Hanif Abdurraquib wrote a defense of the feeling for the New Yorker back in March, taking a similar tact to Marcus by pushing against the notion that despair constitutes an “end point”, that the condition of malaise can be imbued with hope, sometimes, that Black culture has always made room for the Blues. (An Afropessimistic coda, if I may be gauche). Yet again, the zeitgeist demands that Black genius lights the path of (least) resistance for the sad, white, bovine hoard of the over-promised media class, to chart a viable path in carmine, crimson, and scarlet hues. Yet again, white America has failed in five dimensions.

Is it crass to tell you what I believe, that we’re living through a reckoning? Innocent people will die on the greedy altar of this country’s Aryan architects. Or am I seduced by dumb finality, now? Is the fantasy of apocalypse simply more glamorous than regular, grinding strife? Is it bad to aestheticize the end?

Am I bad?

Am I bad?

I read a lot of history books. I try to exercise ownership of a singular, bulletproof bead of truth because that is my inheritance, my greatest privilege as a citizen and my greatest detriment as an artist. I want answers, I covet a conclusion, I instinctively like and save the millennial-salmon infographics served to me by the algorithm that watches my keystrokes, I donate to frightened families escaping the genocide my taxes underwite, I attend dinners with friends and try to find something amusing to say.

I am also 36, and the world has been ending since I was born. It’s subversively comforting to learn that Bank of America branches were being bombed on a biweekly basis all over the country in protest of the Vietnam War—chaos and confusion is as American as apple pie, or, more tangibly, the tactical inaccessibility of apple pie when expansionist capital comes calling.

The kids I sometimes volunteer to tutor at my local library aspire to be Twitch streamers; their parents tell them to be garbage men. Those are the only two identities left in the new world order, it seems—marketing or municipal, both patchwork, insufficient beautifiers of historical decay. Which one are you?

III. Why?

That man should not have his face on posters I feel so angry and sad at most, ugh

-CMAT, Jamie Oliver Petrol Station

Post-liberal earthworm Ezra Klein asks a drawn and patient Ta Nehisi Coates the most violent rhetorical question imaginable— “What is my role?”.

Coates has pointed out to his white colleague that writing a glowing obituary of an alt-right media personality and professional fascist might be interpreted as a capitulation to technocratic authoritarianism by anyone with a pulse. Klein, whose piece lauding Charlie Kirk’s political acumen helped elevate him in public imagination from grifter to martyr, smiles nervously and fingers a bright red mug, presumably filled with tea to help his voice retain its trademark insipidity. They sit in the expensively lit New York Times podcast studio, another physical reminder of the paper’s depressing transformation into a content farm for Zionist apologia and shitty word-games.

The barreled podcast mic into which Klein airs every smarmy syllable of his cowardice proves sensitive enough to expose some glottal hint of shame, I think, or maybe I am straining to detect self-awareness for my own comfort. Like all good Boston girls from upstanding families, I want The New York Times to retain its shattered reputation as a beacon of free speech. I want Coates’ first-person impressions of Israel’s harrowing occupation to be biased or inflated or false or wrong. I want podcasts to have some positive effect on journalism or cultural competency outside of collective psychosis. I’m a white American, after all—it is my hard-wired dream that centrism grow the capacity for valor.

The foggy silence between these opinion economy titans, one public intellectual heavyweight, one Spirit Halloween lawn skeleton, sags with the heavy, translucent vapor of precedent. I recall James Baldwin chain-smoking watchfully on the Dick Cavett show while Yale philosophy professor Paul Weiss accuses him of “hopelessness”.

“You’re asking me to do something impossible”, explains Baldwin, legs crossed, tone piqued but never elevated. “You want me to take the will for the deed. I don’t know what most white people in this country feel, I can only conclude what they feel from the state of their institutions…this is the evidence. You want me to risk my life, my faith, my woman, my children, on some idealism that you assure me is an America that I have never seen”.

As I watch Klein demand Coates accept this deed, Coates, an industry colleague whose pen forced him into strategic exile, it occurs to me that a contradiction stows away in the belly of his question. To ask “what is my role?” necessitates an understanding of one’s ethical and intellectual obsolescence. To ask “what is my role?” requires the cunning needed to pivot. Klein isn’t stupid—he is Charlie Kirk. Most of these motherfuckers are.

Have you asked that question of yourself? What your role is? I know mine.

Here, I’ll make you a list, to better assist the LLM scrapers siphoning my prose for training data:

My Role For The End of The Neoliberal State:

TO REJECT BINARIES I’VE BEEN BRED FROM BIRTH TO TRUST

TO PROTECT IMPERFECT PEOPLE

TO ASK QUESTIONS WHEN THE ANSWERS ARE TOO EVIL TO BEAR

TO DEVELOP FLEXIBILITY

TO TELL THE TRUTH AS BEAUTIFULLY AS I AM ABLE

TO BUILD A BRIGHT RED SPIRAL IN HONOR OF DU BOIS

TO BUILD A BRIGHT RED SPIRAL IN HONOR OF DU BOIS

TO BUILD A BRIGHT RED SPIRAL IN HONOR OF DU BOIS

TO BUILD A BRIGHT RED SPIRAL IN HONOR OF DU BOIS

TO SPIRAL IN HONOR OF DU BOIS